Lung asbestosis Biogarphy

Source(google.com.pk)Given a history of significant occupational asbestos exposure and typical high-resolution CT findings, surgical lung biopsy rarely is needed to establish a diagnosis.13 For patients in whom surgical lung biopsy is performed, the pathologic pattern is that of usual interstitial pneumonia. This is the same pathology occurring in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and may also be seen in pulmonary fibrosis associated with collagen vascular diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis).13 Asbestos bodies are identified by special iron staining of tissue, and the number of these bodies correlates with the severity of fibrosis. Their presence in the lung tissue confirms the diagnosis of asbestosis.

BENIGN PLEURAL DISEASE

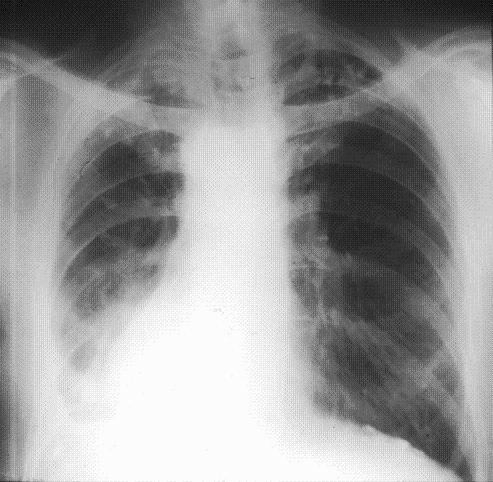

The most common pathologic pulmonary response to asbestos inhalation is the development of pleural plaques (Figure 2). Over time, collagen is deposited in the pleura and may calcify. Most plaques are completely asymptomatic, and there is no evidence that plaques transform into malignant lesions. Plaques occur in approximately 50 percent of persons with heavy and prolonged exposure to asbestos and are, therefore, a marker of asbestos exposure.7 Plaques are not always visible on plain chest radiography, but high-resolution CT will identify up to 50 percent of plaques found at autopsy. However, chest radiography usually is adequate, and the use of high-resolution CT is reserved most often for diagnostic uncertainty or confirmatory testing.7

Chest radiograph of a patient with previous asbestos exposure who has developed pleural plaques (arrows). These plaques are characteristically located symmetrically along the lateral chest wall but also may occur on the domes of the diaphragm.

View Large

Benign asbestos pleural effusions, usually unilateral, are the most common manifestation of asbestos-related pleural disease within 10 to 20 years after exposure.14 When followed over time, effusions may wax and wane. The development of any new pleural effusion mandates a thorough evaluation, including tuberculosis skin testing and diagnostic thoracentesis. Asbestos pleural effusions are exudative.7 However, in cases of exudative pleural effusions, a pleural biopsy may be needed to evaluate for tuberculosis and malignancy. Furthermore, pleural effusion with pleuritic pain may be a manifestation of malignant mesothelioma.15 Therefore, benign asbestos pleural effusion is a diagnosis of exclusion.

DIFFUSE MALIGNANT MESOTHELIOMA

Diffuse malignant mesothelioma is an aggressive tumor derived from mesothelial cells, most commonly of the pleura. It is uniformly fatal, with a median survival time of six to 18 months from diagnosis. Among persons who have worked with asbestos, the lifetime risk of developing mesothelioma is high, although the condition is relatively uncommon, with approximately 2,000 new cases per year in the United States.4 However, even relatively low-level exposure has been associated with an increased risk of developing mesothelioma.13

The presenting symptoms of malignant mesothelioma are vague (Table 1), which often leads to a delay before the patient seeks care. Similarly, the nonspecific nature of the symptoms makes the diagnosis difficult. Chest pain and dyspnea are common initial complaints.16 Chest radiography most often will reveal a large, unilateral pleural effusion. Chest CT will demonstrate the same features; however, irregular thickening of the pleura also may be visible. In more advanced disease, there may be superior vena cava syndrome, Horner's syndrome, dysphagia, or other complications resulting from the propensity of mesothelioma to invade neighboring structures. Pathologic diagnosis can prove difficult, and many cases are misdiagnosed initially.

Palliative radiation therapy can be effective in reducing symptoms, especially from metastases. Current clinical trials emphasize a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, but no regimen has yet been clearly shown to improve survival rates. Recent study has focused on the identification of serum markers (e.g., serum mesothelin-related protein, osteopontin) that may prove useful as screening tools.17,18The Authors

KATHERINE M.A. O'REILLY, M.D., is a pulmonologist at Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, United Kingdom. She received her medical degree from McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, and completed a residency in internal medicine and a fellowship in pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Rochester, N.Y.

ANNE MARIE MCLAUGHLIN, M.B., is a pulmonary fellow at St. Vincent's University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. She received her medical degree from University College Dublin, Ireland.

WILLIAM S. BECKETT, M.D., is a professor of medicine and environmental medicine at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. He received his medical degree from Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, and completed fellowships in pulmonary medicine and occupational medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md.

PATRICIA J. SIME, M.D., is an associate professor of medicine, environmental medicine, an oncology at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. She received her medical degree from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, where she also completed a residency in internal medicine. Dr. Sime served a fellowship in pulmonary medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Address correspondence to Katherine M.A. O'Reilly, M.D., Respiratory Medicine Department, D Level West Wing, Mailpoint 48, Southampton General Hospital, Tremona Road, Southampton SO16 6YD, United Kingdom (e-mail: kateindub@yahoo.co.uk). Reprints are not available from the authors.

Author disclosure: William S. Beckett, M.D., is supported by NIEHS P30 ES01247 and the New York State Occupational Health Clinics Network. Patricia J. Sime, M.D., is supported by NIH RO1HL075432, NIH K08HL04492, and NIEHS P30 ES01247.REFERENCES

1. Peto J, Decarli A, La Vecchia C, Levi F, Negri E. The European mesothelioma epidemic. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:666–72.

2. Work-Related Lung Disease Surveillance Report 2002; Division of Respiratory Disease Studies, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DHHS (NIOSH) number 2003–111, May 2003.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Changing patterns of pneumoconiosis mortality—United States, 1968–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:627–32.

4. Price B, Ware A. Mesothelioma trends in the United States: an update based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program data for 1973 through 2003. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:107–12.

5. Lilienfeld DE, Mandel JS, Coin P, Schuman LM. Projection of asbestos related diseases in the United States, 1985–2009. I. Cancer. Brit J Ind Med. 1988;45:283–91.

6. Peipins LA, Lewin M, Campolucci S, Lybarger JA, Miller A, Middleton D, et al. Radiographic abnormalities and exposure to asbestos-contaminated vermiculite in the community of Libby, Montana, USA. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1753–9.

7. American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis and initial management of nonmalignant diseases related to asbestos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:691–715.

8. van Loon AJ, Kant IJ, Swaen GM, Goldbohm RA, Kremer AM, van den Brandt PA. Occupational exposure to carcinogens and risk of lung cancer: results from The Netherlands cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:817–24.

9. Boffetta P. Epidemiology of environmental and occupational cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:6392–403.

10. Liddell FD. The interaction of asbestos and smoking in lung cancer. Ann Occup Hyg. 2001;45:341–56.

11. Berry G, Liddell FK. The interaction of asbestos and smoking in lung cancer: a modified measure of effect. Ann Occup Hyg. 2004;48:459–62.

12. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease: recommendations statement. Accessed October 3, 2006, at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/tobacccoun/tobcounrs.pdf.

13. Craighead JE, Abraham JL, Churg A, Green FH, Kleinerman J, Pratt PC, et al. The pathology of asbestos-associated diseases of the lungs and pleural cavities: diagnostic criteria and proposed grading schema. Report of the Pneumoconiosis Committee of the College of American Pathologists and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1982;106:544–96.

14. Wagner GR. Asbestosis and silicosis. Lancet. 1997;349:1311–5.

15. Robinson BW, Lake RA. Advances in malignant mesothelioma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1591–603.

16. Antman KH. Natural history and epidemiology of malignant mesothelioma. Chest. 1993;103(4 suppl)373S–6S.

17. Robinson BW, Creaney J, Lake R, Nowak A, Musk AW, de Klerk N, et al. Mesothelin-family proteins and diagnosis of mesothelioma. Lancet. 2003;362:1612–6.

Asbestos (pronounced /æsˈbɛstəs/ or /æzˈbɛstəs/) is a set of six naturally occurring silicate minerals used commercially for their desirable physical properties.[1] They all have in common their eponymous, asbestiform habit: long (ca. 1:20 aspect ratio), thin fibrous crystals. The prolonged inhalation of asbestos fibers can cause serious illnesses[2] including malignant lung cancer, mesothelioma, and asbestosis (a type of pneumoconiosis).[3] The European Union has banned all use of asbestos,[4] as well as the extraction, manufacture, and processing of asbestos products.[5]

Asbestos became increasingly popular among manufacturers and builders in the late 19th century because of its sound absorption, average tensile strength, its resistance to fire, heat, electrical and chemical damage, and affordability. It was used in such applications as electrical insulation for hotplate wiring and in building insulation. When asbestos is used for its resistance to fire or heat, the fibers are often mixed with cement (resulting in fiber cement) or woven into fabric or mats.

Asbestos mining began more than 4,000 years ago, but did not start large-scale until the end of the 19th century. For a long time, the world's largest asbestos mine was the Jeffrey mine in the town of Asbestos, Quebec.[6]

Six minerals types are defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency as "asbestos" including those belonging to the serpentine class and those belonging to the amphibole class. All six asbestos mineral types are known to be human carcinogens.[7][8]

Serpentine[edit]

Serpentine class fibers are curly. Chrysotile is the only member of the serpentine class.

Chrysotile[edit]

Chrysotile, CAS No. 12001-29-5, is obtained from serpentinite rocks which are common throughout the world. Its idealized chemical formula is Mg3(Si2O5)(OH)4.[9] Chrysotile appears under the microscope as a white fiber.

Chrysotile has been used more than any other type and accounts for about 95% of the asbestos found in buildings in America.[10] Chrysotile is more flexible than amphibole types of asbestos, and can be spun and woven into fabric. Its most common use has been in corrugated asbestos cement roof sheets typically used for outbuildings, warehouses and garages. It may also be found in sheets or panels used for ceilings and sometimes for walls and floors. Chrysotile has been a component in joint compound and some plasters. Numerous other items have been made containing chrysotile, including brake linings, fire barriers in fuseboxes, pipe insulation, floor tiles, and rope seals for boilers.[citation needed] .

Amphibole

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Lung asbestosis Wallpaper Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment